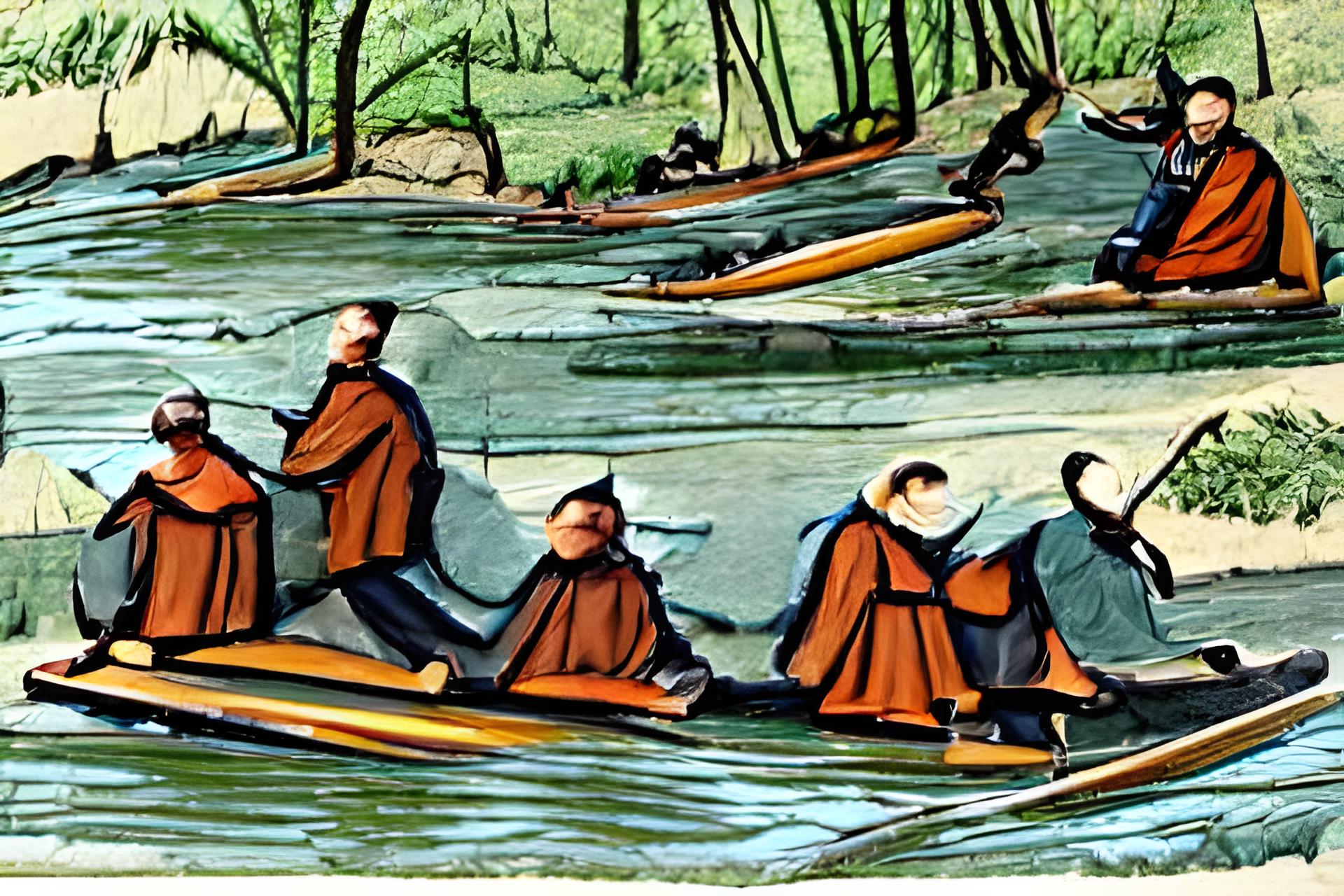

So I have heard. At one time the Lord Buddha, the Blessed One, the ascetic Gotama, and his five venerable ascetic disciples, were being ferried from Cittapālo to Kāsapo along the Titopañño river. The trip by ferry had lasted many hours, and hours on the ferry still remained. Word had begun to spread through the countryside of the Lord Buddha’s journey.

The Buddha was looking out over the water. He swept out a horizontal arc with his hand. "Look at this river," he said. And the venerable ascetic disciples looked.

"The mind is like this river, venerable disciples."

Silently, the disciples considered the river.

After a minute or two, venerable disciple Ānanda said, "Lord Gotama, the mind is like this river because, like the river, the mind never stops flowing."

The Buddha smiled. Ānanda continued, however.

"The mind is like this river because, from moment to moment, the mind changes. Yet mind is also like this river because, from moment to moment, the mind stays the same."

The Buddha gently nodded and looked away, his face now blank. "Yes, Ānanda," he said, while facing the river, "that was what I was going for."

"The mind is like this river because it never begins, nor does it ever end—"

“Ānanda, you are getting carried away,” said the Buddha.

The other venerable disciples turned their heads away, apparently to investigate a sound coming from the shore.

“You must learn to stop while you are ahead,” the Buddha continued. “It's just that rivers do, in fact, end. We disembark from this ferry precisely where the river ends — at the delta."

"You are right, as usual, Lord Gotama," replied Ānanda.

For a time there was no sound except for the gentle splashing of the water onto the hull of the ferry, and the whisper of leaves dancing in the wind.

Meanwhile, Ānanda thought some more. And then again he spoke:

"The mind is also like this river because although it is turbulent on the surface it is still and calm below. And, yet, for the man who is afraid to leave his boat, he will never experience the tranquility of being beneath the ripples and waves, and will instead remain transfixed by the reflections on the surface—"

"You're forcing it, Ānanda," said the Buddha. "You're trying too hard. Though the essence of what you say is nevertheless true, and I cannot, in my wisdom, deny it... perhaps you should consider..." the Buddha paused to think.

"Yes, Lord Gotama. Sorry," said Ānanda, and he went quiet for a while.

The other disciples were gazing away, into the trees, pretending to look for howler monkeys.

"Um... Lord Gotama?" said Ānanda.

The Buddha turned to look at Ānanda, who was looking at his feet and crossing his toes.

"The mind... is like this river..." he said, waiting for the Buddha to say something, but the Buddha did not.

Ānanda's words then burst out of him like a flock of starlings. "The mind is like this river because there are fish in the river that arise to the surface causing ripples in the water but in reality the fish live underneath the surface and although they cannot be seen when they are underneath they are always there and thus we realize that the fish are thoughts and the surface of the river is the consciousn—"

"Ānanda — please," said the Lord Buddha. He then smiled and offered a common refrain: “Those who know do not speak, and those who speak do not know."

A long time passed in silence. The afternoon sun grew strong and red.

As the ferry drifted along the Titopañño river, the Lord Buddha and his five venerable ascetic disciples passed a fisherman's boat. There was a lone fisherman inside who was pulling up his fishing net. The net was full of small fish. The Lord Buddha asked the fisherman, "Where did you cast this net to catch these small fish?"

"I placed the net just underneath the surface," replied the lone fisherman to the Lord Buddha.

The Buddha expressed his gratitude and thanks to the lone fisherman and the ferry continued on further.

They passed another fisherman's boat. There was yet another lone fisherman, pulling up a net full of medium-sized fish. The Lord Buddha asked the fisherman, "Where did you cast this net to catch these medium-sized fish?"

"I placed the net half-way deep in the river," said the lone fisherman to the Blessed One.

"I think I know where this is going," said Ānanda to himself.

The Buddha expressed his gratitude and thanks to the lone fisherman and the ferry continued on further.

They passed yet another fisherman's boat. There was a third lone fisherman, this time pulling up a net full of large fish. The Lord Buddha asked the fisherman, "Where did you cast this net to catch these large fish?"

Ānanda said, “He must have cast it near the bottom of the river," before the fisherman could reply.

"I did indeed," replied the lone fisherman. "But how did you know? Have you fished in this river before?"

"I know because the mind is like this river," said Ānanda, solemnly, his face assuming a frown, "The fish are concepts, concepts that contain other concepts. The small fish are the little concepts that abide near the surface — in other words, near surface consciousness. The medium-sized fish are the medium-sized concepts that 'eat' the smaller fish, in other words, they contain the smaller concepts. And the large fish represent the biggest concepts of all, the concepts that include all the others but that which reside in the deepest depths of the mind — er, I mean, the river..." Ānanda tripped over his words a little.

"Concepts?" said the fisherman. "But these are fish. Wait a minute,” the fisherman seemed to have an idea. “Are you the Buddha? The ascetic Gotama? I have heard about you. But you are different than I was imagining.”

"Well I’m not exact—"

"I am the ascetic Gotama," announced the Lord Buddha. "He who spoke is called Ānanda. Ānanda is my venerable disciple... I suppose."

The Buddha expressed his gratitude, thanks and apologies to the fisherman and the ferry pressed on.

It was nearing the end of the day and the ferry began to slow as it approached a river delta, where the it was to lay its anchor and where the Lord Buddha and his venerable disciples were to disembark. Beyond the delta the river spilled out into the sea.

Contemplating the delta, its features, details, and formations, Ānanda noticed the river dissolving, emptying itself into the vastness of the sea. Ānanda looked at the Lord Buddha. He could not help himself.

"Do not say it, Ānanda, do not say it," said the Buddha.

Ānanda barely lifted his hand as he pointed to the ocean.

"Please do not say it, Anānda," pleaded the Buddha.

Ānanda peeped, "...the collective consciousness?"

The Buddha put his face in his hands.

Ānanda tried again. "No... it's rebirth, because the river flows into the ocean, and continues on in a different form, before becoming a river again..."

He kept going. "And the strange creatures at the ocean floor — perhaps those are the devas? Celestial beings, guardian spirits of the earth, inhabiting other realms, only accessible to those who have gone forth into the depths of the mind? When the river water can flow to the bottom of the sea?"

"Ānanda," said the Buddha, calmly, "you are taking what I say both too literally and yet not literally enough. If you were careful in your thinking you would have noticed that the river water does not just empty itself into the sea. The river also evaporates into the sky; becomes clouds, rains, and icebergs; and forms drinking water all across the world. Some of the water molecules will even break apart to form oxygen and hydrogen..."

"Huh?" said Anānda. "Molecules?"

"My point being that you are thinking about rebirth in a simplistic way. Humble yourself. You are trying to play the wise man, but just because you know one thing does not mean you know everything."

The Buddha continued. "If you are not careful with your words, Ānanda, they will take teachings like yours and attribute them to me. And they will assume that because I knew one thing, that I knew everything else, too. They will say that I was perfect, pure, the greatest man to ever live. But that is not so, Ānanda, it is not so."

"I hope that someday my teachings will be explained in just a few succinct truths," said the Buddha, "or else they will proliferate. And if they proliferate, the lesser ones will crowd out the important ones. Such teachings would surely form the basis of some kind of religious text — long-winded, dogmatic, and stuck in the past."

The Buddha placed his hand around his chin. "Well, except, I suppose I'd have to explain the jhānas too..." He paused, frozen.

And then his face became animated again. "But I would keep those explanations brief, so as not to be misunderstood. For example, as a first instruction, ‘putting mindfulness to the front' is rather clear, no?"

Ānanda and the other venerable disciples nodded, acknowledging the Lord Buddha's wisdom.

One disciple whispered to another, "By ‘front’ the Lord must mean the 'front' of the body, near the face, by the nose, no?"

"I think he means to the 'front' of the mind, as in the forefront, a priority," said the second disciple, out of earshot to the Buddha. “I’m sure we’ll figure it out later.”

The Buddha continued talking, stepping off of the ferry and onto dry land.

“I teach only what truly matters — aniccā, anattā, and duhkha. Too many teachings, venerable disciples, are like too many channels for the mind to flow through. The mind has only so much vigor, only so many places it can go. Every new teaching which is incidental to the first, such as those of celestial beings, spirits, realms of heaven or hell, rebirth, astral powers, arcane rules and responsibilities, each of these leaves the mind with less power with which to flow to those parts that matter.”

Ānanda thought "the mind is like this river," but didn’t say it. He silently stepped off of the ferry, following the Buddha to Kāsapo.